How Parody Defense Triumphed Over Trademark & Copyright Claims: Lessons from Louis Vuitton vs. My Other Bag on Fair Use, Dilution, and Consumer Confusion

Introduction:

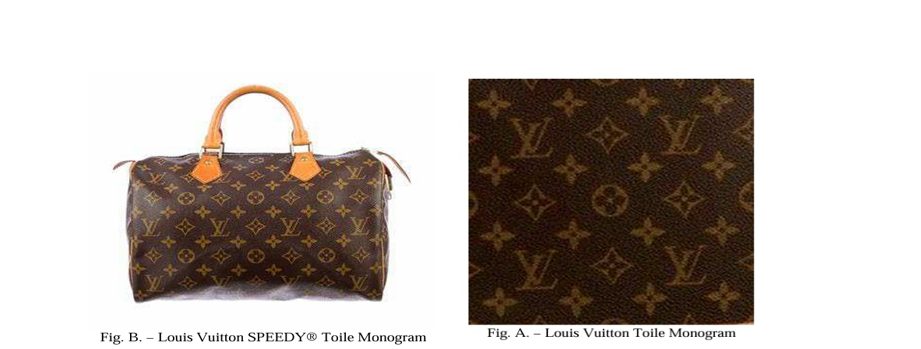

Louis Vuitton Malletier, S.A, “Louis Vuitton”, used to make and sell Louis Vuitton bags (Fig. A and Fig B). It is known for its high-quality handbags which was often sold for thousands of dollars. Whereas, My Other Bag, Inc. founded in 2011. They also used to sell their bags. The price of their bags ranges from just thirty to thirty-five dollars. My Other Bag used to sell canvas bags having caricatures as parody of iconic designer handbags on one side and “My Other Bag” written on the other. They were inspired from novelty bumper stickers, which can be seen in inexpensive car having caricatures of expensive car and written as “my other car”.

In one of the “MOB” tote bags, they depicted on one side with the drawings using simplified colours and patterns that resemble Louis Vuitton’s famous bag designs, but replaced the interlocking “LV” and “Louis Vuitton” with “MOB” and “My Other Bag”. Whereas, on other side of bag, they just wrote “My other Bag” (Fig. C and Fig. D). Louis Vuitton filed for trademark dilution, and trademarks infringement under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c) with claims of copyright infringement against the MOB. MOB filed a motion for summary judgment regarding the claims made by Louis Vuitton. In turn, Louis Vuitton requested summary judgment on its claims of trademark dilution and copyright infringement.

Arguments on behalf of Louis Vuitton:

Louis Vuitton claimed that MOV is liable for trademark dilution under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c). It claimed that after watching the bag people develop a sense of association between the MOB Bags and brand reputation of Louis Vuitton, as logo, colour, monogram was resembling with the Louis Vuitton’s handbags. It is also leading to gradual diminishment of their mark’s acquired ability to clearly distinguish one source through any unauthorised one.

Louis Vuitton placed their reliance on Louis Vuitton Malletier, S.A. v. Hyundai Motor Am. In which the Court rejected the defence of Hyundai in which they argued that parody is used and based on large part of testimony from Hyundai representatives that established that Hyundai did not intend for the advertisement to make any remarks regarding Louis Vuitton, contradicting their argument that they leveraged the trademark for parody purposes.

Louis Vuitton again argued that MOB’s bags cannot be a parody because they can used their own trademarks for parody but here, they used the Louis Vuitoon’s trademarks. Also, they argued that fair use exception won’t be apply to Mob’s totes as MOB uses Louis Vuitton’s trademarks “as designation of source for their goods. Because whoever used to see towards the MOB bags they shall recognise the signs of Louis Vuitton.

The Summary Judgement:

Jesse M. Furman, J. cited that summary judgement comes into picture when, at the request of any party, there is lack of genuine dispute in any material fact arose after recording of evidences. The party seeking summary judgement bears the initial burden of demonstrating the absence of genuine issue of material fact. Whereas, when both side file for summary judgement, the district court is required to assess each motion on its own merits and to view the evidence in the light most favourable to the party opposing the motion. Whereas, the defendant is required to present sufficient evidence that raises significant doubt regarding the essential facts.

Whereas, in assessing whether dilution by blurring is likely to occur under New York law, a court “may consider all relevant factors given:

“(i) the similarity of the marks; (ii) the similarity of the products covered; (iii) the sophistication of the consumers; (iv) the existence of predatory intent; (v) the renown of the senior mark; and (vi) the renown of the junior mark.”

On the other hand, federal law provides that certain uses of a mark “shall not be actionable as dilution by blurring,” including:

Any fair use . . . of a famous mark by another person other than as a designation of source for the person’s own goods or services, including use in connection with . . . identifying and parodying, criticizing, or commenting upon the famous mark owner or the goods or services of the famous mark owner. 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c)(3).

Trademark dilution: Hon’ble court held that to succeed in dilution claim against anyone in federal law, a plaintiff need not show economic injury but must prove first that the infringed trademark is distinctive in its nature. Nextly, there should be likelihood of dilution due to blurring.

The esteemed court determined that while “parody” lacks a statutory definition, it has been clarified through various judicial rulings. These rulings emphasize that “A parody must deliver two concurrent yet contradictory messages: it imitates the original, while also indicating that it is not the original and is, in fact, a parody.”

Hon’ble court rejected the Hyundai case argument citing that in that case, they did not intend to parody against the Louis Vuitton. The concept that My Other Bag’s bag represents a message that extends beyond just being copies of LV’s bags does not undermine a solid defense of parody. However, is immaterial, If Louis Vuitton does not find the comparison of bags funny.

Whereas, on the argument of “not being a designation of source for their own products”, hon’ble court held that the overall design of MOB’s tote bags, “My Other Bag” on one side and differing caricatures on other side, and also that it always bears a luxury brands for caricature, there is no basis to conclude that MOB uses Louis Vuitton’s marks as an identification of origin for its MOB’s bags.

Hon’ble court held that fair use exception of parodies in Section 1125(c)(3) will not apply as MOB used the Louis Vuitton’s mark as a designation of source for its own goods. Also, court cannot ignore that parody has been used as a trademark. The louis Vuitton has failed in demonstrating that the distinctiveness of its famous marks is likely to be harmed by parody. That’s how Louis Vuitton has failed to make out ta case of trademark dilution by blurring.

Trademarks Infringement: Hon’ble court reiterated the eight-factor balancing test for determining the likelihood of confusion, held by Judge Friendly in Polaroid Corp. v. Polarad Elecs. Corp., 287 F.2d 492 (2d Cir. 1961). It is held that the question should be whether by looking at the products in its totality, consumers are likely to be confused or not. The eight factors are:

- strength of the trademark;

- similarity between the marks;

- proximity and competitiveness with one another;

- Proof the senior user could market a competing product;

- evidence of actual consumer confusion;

- evidence that the imitative mark was adopted in bad faith;

- respective quality of the products; and

- sophistication of consumers in the relevant market.

Beginning with the first, it is held that Louis Vuitton’s marks are famous. But again, said that the strength of their marks is the sole reason why the use of a parody over it can easily be understood by the common people because of its popularity. Secondly, on the similarity, there is indeed similarities between the marks but there are obvious differences too. The way MOB is drawn is comical, and “MOB” has replaced “interlocking”. On the other side, it says “My other bag.” Hence the overall setting convey that this is a joke and not the real thing. Also, the consumer base is totally different. One is selling for Thousands of dollars whereas other being sold just for thirty to thirty-five Dollars. On the fifth factor, that evidence of actual consumer confusion. No customers truly thought that the MOB’s totes were genuinely made or endorsed by Louis Vuitton. For the sixth factor, it was not shown that defendant acted with an intent to capitalize on consumer deception on plaintiff’s good will. Instead, the intent was there necessarily to amuse but not to confuse the public.

Copyright Infringement:

The hon’ble court concluded that the use by MOB of copyrightable elements qualifies as a matter of law as “Fair use”. The Court assesses four factors by considering the overall circumstances:

17 U.S.C. § 107:

- the purpose and character of the use, determining whether it is for commercial gain or for educational, nonprofit purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted content;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect upon the potential consumers for the copyrighted work.

On the first factor, Hon’ble court held that although commercial use must be of a fair use but parody can also be of fair use. On secondly, in parody case, it mostly happens on copying publicly known works as expressive works. In the third place, MOB’s application of Louis Vuitton’s designs is justifiable concerning the intended use — indeed, MOB’s totes must effectively evoke Louis Vuitton’s handbags to be meaningful. Finally, on the market replacement, after analysing the consumer base, it is evident that My Other Bag never intended to replace the Louis Vuitton’s designer bags or its consumers.

Conclusion:

The court granted summary judgment in favour of My Other Bag, Inc., and denied all of Louis Vuitton’s motions. The judge determined that MOB’s totes represented a parody and that their utilization of Louis Vuitton’s trademarks qualified as “fair use”. The court noted that the joke was evident and that the tote bags were not meant to be a substitute for a genuine Louis Vuitton bag but rather a playful commentary on the luxury brand.

Author:–Pradeep Yadav, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us at support@ipandlegalfilings.com or IP & Legal Filing.

End notes:

Cliffs Notes, Inc. v. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publ’g Grp., Inc., 886 F.2d 490, 494 (2d Cir. 1989)

(Johnson v. Killian, 680 F.3d 234, 236 (2d Cir. 2012)

Ergowerx Int’l, LLC v. Maxell Corp. of Am., 18 F. Supp. 3d 430, 7 451 (S.D.N.Y. 2014).

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 325 (1986).

Louis Vuitton vs. My Other Bag, 156 F. Supp. 3d 425 (S.D.N.Y. 2016)